THERE ARE FOUR INSTANCES OF GHOSTS APPEARING IN SHAKESPEARE" PLAYS, (five if you include the final appearances of ghosts at the end of Cymbeline which I'm not going to include here as they play a passive 'background role).

They include the ghosts

1) who appear in Richard III's dream before he is killed in battle.

2) The ghost of Banquo who was murdered by Macbeth. Macbeth also sees apparitions of the future kings of Scotland.

3) The ghost of Julius Caesar who appears to Brutus before his own suicide.

4) The ghost of Hamlet's father who appears at the beginning of the play.

In all of the above plays (apart from Hamlet), the ghosts appear only to certain individuals whose behaviour is strongly influenced by this unnatural encounter. In Hamlet, the ghost first appears to Hamlet's friends, Bernardo and Marcellus before appearing later to Hamlet himself.

Another common factor concerning the ghosts is that they are almost all the spirits of people who have been killed by Brutus, Macbeth or King Richard. (Hamlet's father was killed by his brother Claudius, leaving Hamlet innocent of the knowledge of this death until the ghost informs him of such.)

Iconic painting of 18th cent. actor Edmund Kean playing Richard III seeing the ghosts before the battle of Bosworth.

In terms of the history of the composition of WS's plays, the first ghosts who appear are in Richard the Third (c.1592-3). Here, on the night before the fateful Battle of Bosworth (Act V) the ghosts of Henry VI and his son, Edward, Richard's brother, Clarence, the Lords Hastings, Rivers, Grey and Vaughan as well as those of the two Princes in the Tower and Richard's wife, Lady Anne, appear to torment the king in his sleep. And torment him they do! They all end their maledictions, "Despair and die!" - a prediction that comes true.

On the other hand, these same ghosts appear in the dreams of Richard's opponent, Henry of Richmond, the future King Henry VII. In contrast to Richard's troubled dreams, the same ghosts wish him to "Live and flourish" and that he should "... fight, and conquer for fair England's sake!"

The next time WS uses ghosts is in Julius Caesar (c.1599). Here, the ghost of the murdered Julius Caesar appears to Brutus who, like Richard III, is resting before the final battle which will be fought on the Plains of Philippi. The ghost promises Brutus that he will see him later on the battlefield leaving Brutus to exclaim, "O Julius Caesar, thou art mighty yet! Thy spirit walks abroad, and turns our swords in our own proper entrails." This, of course, is highly prophetic as soon after Brutus does indeed kill himself using his sword.

Approximately two years after writing Julius Caesar, WS used the ghostly motif once again. This time the ghost of Hamlet's father appears at the beginning of the play. The ghost informs Hamlet that his father was killed by his brother Claudius in order to rule Denmark in his stead. It is this knowledge that spurs Hamlet on, albeit sometimes reluctantly at times, to seek revenge.

In 'the Scottish play,' written in 1605-6, (dated through references to the Gunpowder Plot, 1605) Macbeth is completely thrown off balance when he is faced with the gory and ghostly remains of his past friend, Banquo. This scene happens, when Macbeth, accompanied by his wife and several of his chief lords are celebrating Macbeth's recent ascent to the throne. Despite this crowded scene, it is only Macbeth who sees the ghost, a vision that completely derails him. Later, the three weird sisters/witches, in response to Macbeth's request, show him more apparitions in the form of eight future kings of Scotland. This unsettles him even more and from now on, he is hell-bent on fighting his way through to his final demise.

Next time: Hamlet's mother, Gertrude.

For comments: Facebook or: wsdavidyoung@gmail.com

One of the reasons the First Folio is so recognisable is because of the iconic engraving of Shakespeare on the title page. This was done by Martin Droeshout (1601-c.1650), an engraver who didn't know the Bard personally and who was only 15 years old when WS died. He must have copied it from an existing portrait but it must have been a fairly accurate representation as WS's friends and fellow-actors and compilers of the First Foio, Condell and Hemminges, approved of it.

This book is called a folio (Latin for 'leaf') because its leaves or sheets of paper were folded only once as opposed to twice as in a 'quarto. This meant that the original First Folio was a larger book than the normal size one of the time.

Copy of the First Folio in the Bodlean Library, Oxford

Many of the plays that first appeared here were probably based on WS's manuscripts or prompt-books owned by his acting company, as well as from faulty quarto copies of the original plays. It is also likely that a paid scribe copied them for the printer (William & Isaac Jaggard {son})before they were finally produced. All of this meant that several mistakes crept in which were eventually removed in later folio copies of WS's plays.

THE SECOND FOLIO was printed nine years after the first in 1632. and was printed by Thomas Cotes for Robert Allot, Smethwick, Apsley, Richard Hawkins and Richard Meighen. It is a faithful copy of F1 but some of the original mistakes and proper-names and stage directions have been corrected.

THE THIRD FOLIO was printed in 1663 and contained further corrections as well as the text of Pericles which was missing in F1 and F2. This third Foli is fairly scarce today because a number of unsold copies were burned in the Great Fire of London in 1666. This folio also contained seven other plays including The London Prodigal, The Puritan Widow and A Yorkshire Tragedy.

THE FOURTH FOLIO, printed in 1685 is a reprint of F3 and contains more corrections as well as adding its own new mistakes. It also contains Pericles and the extra plays which appeared in F3.

Note: The second, third and fourth folios are not always considered by literary critics etc as they were printed without any reference to the early quartos or manuscripts.

Next time: Ghosts in WS plays.

For comments: Facebook or: wsdavidyoung@gmail.com

THE FIRST FOLIO - the first collection of Shakespeare's plays was first published in November 1623, seven years after his death. It was a large book, made up of folded folios of paper and was compiled by two of WS's fellow actors, John Hemminges and Henry Condell. In the preface they wrote that they were publishing this book 'without ambition either of self-profit or fame, only to keep the memory of so worthy a friend and fellow alive as was our Shakespeare.'

Memorial to Hemminges, Condell and Shakespeare in Love Lane, in the City of London.

It is thought that about one thousand copies were printed, of which 230-240 copies survive until today. The First Folio originally cost one pound sterling, about $50 in today's money. In 2001, a copy sold for 4.3 million pounds! It was printed and published by William and Isaac Jaggard, with Edward Blount as an additional publisher. It included thirty-six plays, of which eighteen (some say fourteen), had already been published as Quartos. This meant that Hemminges and Condell succeeded in rescuing eighteen (or twenty-two) plays from being lost forever.

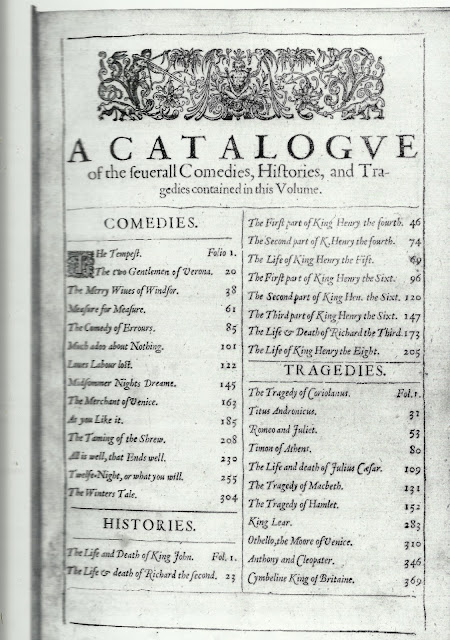

The Folio divided up the plays into Comedies, Histories and Tragedies but it didn't include all of WS's plays. Those that didn't appear include Pericles and The Two Noble Kinsmen (partly written by WS) and possibly Sir Thomas More and Love's Labours Won and Cardenio (probably written by WS and John Fletcher. Another play, Edward III, has been credited to WS, but that was only in 1656 and today is not accepted as a genuine WS play by certain academics.

Incidentally, the printer miscalculated the space he needed for Timon of Athens in the First Folio. As a result, many of the play's lines were cut in half and rewritten as verse so that they could easily be fitted in the available space.

Today, of the 232 known copies of the Folio known to be in existence, 82 of them are in the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC.**

A copy of the First Folio in the Folger Library, Washington DC.

One of the most well-known features of the Folio include the poetic dedication written by WS's fellow-playwright, Ben Jonson, which includes the following lines:

[Shakespeare was] not of an age, but for all time.

and

Soul of the Age! The applause, delight, the wonder of our stage!

and

How far thou didst our Lyly outshine,

Or sporting Kyd, or Marlowe's mighty line.

Another well-known feature in the First Folio is the iconic engraving by Martin Droeshout. Since this engraver was only 15 years old when WS died in 1616, he must have based it on an unknown contemporary drawing. However, I will deal with this in more detail in my next blog.

Ben Jonson and his poetic preface

**Personal comment: I think it is a shame that the Library has aimed to collect as many copies of the Folio as it can. I believe that copies of this historic book should be distributed throughout the world as much as possible so that more people can enjoy experiencing it and not just the Folger Library and private collectors. In other words, why can't the Folger Library 'lend out' copies of the Folio to other libraries and institutions around the world?

Next blog: More about the Folio.

For comments: Facebook or wsdavidyoung.@gmail.com

In his plays, Shakespeare makes the use of five friars:

Friar Francis in Much Ado About Nothing

Friar Lawrence in Romeo and Juliet

Friar Peter in Measure for Measure

Friar Thomas in Measure for Measure

Friar John in Romeo and Juliet

In this blog, I am going to concentrate on the first two, Friars Francis and Lawrence.

FRIAR FRANCIS is the well-meaning friar who has the job of marrying Hero and Claudio in Much Ado. When Hero faints after being slandered by Claudio at the wedding, the friar suggests that it is published that Hero has died of grief. Claudio feels remorse and later marries the 'revived' Hero. In the final scene, not only does Friar Francis join Hero and Claudio in holy matrimony, but he also does the same with Beatrice and Benedick, the two loquacious heroes of the play.

Friar Francis marrying Hero & Claudio in Kenneth Branagh's version of "Much Ado about Nothing."

FRIAR LAWRENCE is another-meaning friar who secretly marries Romeo and Juliet. At the beginning of the play in Act II, sc.iii, he foreshadows the grim ending of the play when he refers to the life and death of plants and how they can be compared to people. Unfortunately for the friar, and even more so for our 'star-crossed lovers,' his plan becomes unstuck as both Romeo and Juliet die in the end.

Friar Lawrence in Zefferelli's film version of "Romeo and Juliet."

Question: Was this friar, despite his good intentions, a good guy? After all, it was his plan that led to the untimely demise of Romeo and Juliet.

Interestingly enough, both of these friars are called on to act as the 'middlemen' in these two plays. In a way, they both 'play God' and use the device of shamming death to try and bring a joyful solution to the conflict. Unfortunately, in R&J it doesn't work out that way.

Another point is that these friars are representatives of the Roman Catholic Church. This was certainly not an institution that was 'flavour of the month' during the **Jacobethan period. They both play a vital and pivotal role in both of these plays.

Pete Posslethwaite as the Friar in "Romeo and Juliet."

**I have recently discovered the word, 'Jacobethan,' a word that covers Shakespeare's life time and playwriting career. I will be using it from now on quite happily.

Next time: The First Folio of Shakespeare's plays.

Comments: Facebook or: wsdavidyoung@gmail.com