To make a change from my usual blogs about Shakespeare, this blog is about a special offer by Amazon in connection with my documentary novel about catching the top Nazi, Adolf Eichmann. For the next few days, this book in its Kindle version will be FREE. Exploit this opportunity while it lasts!

The title:Six Million Accusers comes from the opening speech by the Israeli Prosecutor-General, Gideon Hausner, at Eichmann's trial in Jerusalem in 1961. In it he declared:

"When I stand before you here, Judges of Israel, to lead the prosecution of Adolf Eichmann, I am not standing alone. With me are SIX MILLION ACCUSERS. But they cannot rise to their feet and point an accusing finger towards him who sits in the dock and cry: I accuse. For their ashes are piled up on the hills of Auschwitz and the fields of Treblinka..."

As you may recall, the Israeli secret service, the Mossad, spent fifteen years tracking down this evil man after the end of World War Two. Despite their efforts, together with those of famous Nazi hunters such as Tuvia Friedman and Simon Wiesenthal, they were unsuccessful.

Then one day the Mossad received a tip-off about where Eichmann was hiding out in the slums of Buenos Aires from a surprising and completely non-professional source. The rest, as they say, is history.

Back Cover Blurb

This novel has been highly praised on Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk and I was even invited to England last year by the BBC to give seven interviews on the radio about it.

Exploit this chance and tell all of your friends about it.

Read and send comments to: wsdavidyoung@gmail.com

Once upon a time there was a lady called Delia Salter Bacon. She was born in a frontier cabin in the backwoods of Ohio in 1811 and was the daughter of a minister who had a vision. When the vision faded away the Bacon family returned to New England where some twenty years later she became a school teacher in New York, Connecticut and New Jersey.

While she was living in New York Delia developed a love of the theatre and even persuaded the famous Shakespearean actress, Ellen Terry, to help her write her play, The Bride of Fort Edward. This play was based on the true story of Jane McCrea, a young bride who was killed by Indians in 1777 while on her way to meet her fiance. Even though the play was praised by Edgar Allan Poe it bombed commercially.

Modern reprint

In 1846 Delia fell in love with a minister called Alexander MacWhorter but her older brother, Leonard, forbade her to marry him. The minister was tried by the Church for "dishonourable conduct" and Delia was forced to leave New Haven for Ohio as a result of nasty public opinion. Despite this setback, six years later she became a distinguished English Literature lecturer and gave talks all over the eastern USA.

It was during this period that she began to question who really wrote Shakespeare, i.e. she became seriously involved in the Shakespeare Authorship Question, (a topic that has been dealt with on this site a few entries ago). She also became friendly with Nathaniel Hawthorne, the author of The Scarlet Letter, and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

As her involvement increased, so did her desire to sail to England and visit Stratford-upon-Avon to see if the Bard really existed and if he was indeed the author of the works in his name. Her basic theory was that the real author was Sir Francis Bacon (no family relationship), together with Sir Walter Raleigh and Edmund Spenser. She found it impossible to believe that WS, that 'ignorant, low-bred, vulgar country fellow, who had never inhaled in his life one breath of that social atmosphere that fills his plays' was really responsible for the writing of Macbeth, King Lear and the rest of the Shakespeare canon.

She managed to raise enough money for her project and in 1853 sailed to England. She was to remain there for three years during which time she wrote her magnum opus, The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakespeare Unfolded.Towards the end of her stay, while she was a sick woman, she went to visit WS's grave in Trinity Church, Stratford. There one night, armed with a shovel and a lantern, she planned to open his grave and hopefully find evidence that would confirm her theory. Perhaps the famous curse on the gravestone:

Good friend for Jesus sake forbeare

To digg the dust encloased heare

Blessed be ye man yt spares thes stones,

And cursed be he yt moves my bones.

prevented her from carrying out her plan. As the dawn broke she left the grave untouched and returned to her lodgings.

Shakespeare's gravestone, complete with curse in Holy Trinity church,

Stratford-upon-Avon

She returned to the USA some time after, a very sick woman, and was hospitalised in an asylum. The book which she had written in England was published, but to her great disappointment did not sell well at all. She died in 1857 believing that she was no longer Delia Bacon but 'the Holy Ghost and surrounded by devils.'

Modern reprint

Her obsession that Sir Francis Bacon (and others) had written Shakespeare did not die with her. The English Bacon Society was established in 1885 and an American one in 1892.

For comments, please write to: wsdavidyoung@gmail.com

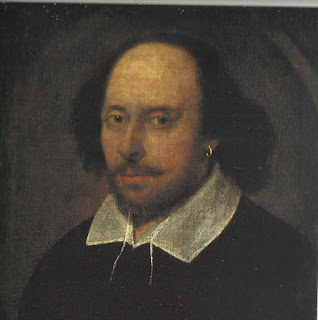

Last time we talked about the classic Droeshout picture of the Bard and about whether it was a true likeness of the man or not. This time I'll show you a few more portraits and leave you to see which one you like best and think is genuine.

Perhaps the CHANDOS portrait is thought to be the closest one to the iconic Droeshout one. This one is so-called because it was once owned by the Dukes of Chandos and was painted between 1610-1613. This means it could be a genuine likeness. It was the first portrait donated to London's National Portrait Gallery when it opened in 1856. We don't know who painted it but some people think that WS's friend and actor, Richard Burbage, was the painter. In 1719 George Vertue, the 18th cent. engraver and antiquary, claimed it was painted by John Taylor, a contemporary child-actor, and that the Droeshout portrait was based on it.

Tarnya Cooper, a curator at the National Portrait Gallery claims that the Chandos portrait is a genuine and true likeness of the Bard.

Another famous portrait of the Bard which looks very similar to the Chandos one is the FLOWER portrait. It is so called because it was presented to the Royal Shakespeare Theatre Gallery in 1895 by Mrs. Charles Flower.

Although it is dated 1609, it was shown in a 1966 x-ray to be something else completely. The x-ray showed that the Flower portrait had been painted on top of a 16th cent. portrait of the Madonna and Child and John the Baptist. The fact that it isn't a genuine portrait was shown again when it was investigated in 2005 and proved that it had been forged sometime during the 19th cent. Tarnya Cooper of the National Portrait Gallery thinks it was copied from the Droeshout one and she claims that it was painted sometime between 1818 - 1840.

Another WS portrait is the lesser-known COBBE one. This portrait is so called because it was owned by Charles Cobbe, the Anglican Archbishop of Dublin, (1686-1765). It was first shown to the world in 2006 and since then its likeness to the Bard has been a bone of contention between the various Shakespearean scholars.

Prof. Stanley Well, writer and Hon. Pres. of the WS Trust, and Gregory Doran, the artistic director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, believe it to be genuine whereas Tarnya Cooper of the NPG claims that it is a portrait of another Warwickshire writer, Sir Thomas Overbury, the 17th cent. poet and essayist who was murdered in the Tower of London in 1613.

Finally, perhaps the portrait that is the least similar to the famous Droeshout one is the SANDERS one. This portrait has a label on the back stating it was painted in 1603 and it's so called as it was owned by a John Sanders, an alleged friend of the Bard. It is possible that WS and Sanders knew each other and that one of the Sanders' family married Anna, one of John Hemmings' (co-compiler of the First Folio and fellow WS actor) cousins.

This portrait was first exhibited in 2001 and it has been very thoroughly investigated since in order to check its authenticity.

Even though it looks nothing like the classical image we think of when we imagine the writer of Macbeth etc., the experts have found it contains 16 facial points that it has in common with other portraits.

Now after all that, which portrait one is the genuine one?

Please comment on: wsdavidyoung@gmail.com

OK, slight exaggeration. He didn't actually write one thousand plays; it was nearer three dozen. However, he certainly inspired many others, the number of which may easily add up to one thousand. However, today I don't want to talk about his skill as a dramatist but about his face, or more exactly, the various portraits of his face.

For those who have been following these pages, you will see that there are nearly as many questions about his portraits as there are about who really wrote his plays. The most famous, even iconic portrait is the one above - the one that appeared in the front of the 1623 First Folio, the first collection of his plays. This book was compiled by his fellow actors, John Hemminges and Henry Condell and the engraved portrait was the work of the engraver, Martin Droeshout, 1601-c.1650.

The First Folio was first published seven years after WS's death and as the engraver had never met the playwright, he had to base his work on a contemporary portrait. Nevertheless, the experts generally agree that this is a genuine likeness as both the compilers and his fellow actor, Ben Jonson (and maybe his wife, Anne Hathaway) accepted this portrait for the front of the book.

Apart from questioning if this portrait is a true likeness, Droeshout's engraving has been the subject of much criticism.

It has been said that the head is too large for the body; it looks like "an egg on a plate" and that the jerkin is back-to-front. WS critic, J. Dover Wilson called it a "pudding faced effigy" while another critic, Samuel Schoenbaum wrote that:

"it had a huge head [which] surmounts an absurdly small tunic with oversized shoulder-wings...light comes from several directions simultaneously: it falls on the bulbous protuberance of his forehead - that 'horrible hydrocephalous development' as it has been called - creates an odd crescent under the right eye and illuminates the edge of the hair on the right side."

The Canadian critic, Northrop Frye said it made the Bard look "like an idiot" while the 18th cent. actor, John Philip Kemble thought that the portrait was a "despised work." The 20th cent. critic, Honan Park (1928-2014) described the portrait thus:

"If the portrait lacks the 'sparkle' of a witty poet, it suggests the inwardness of a writer of great intelligence, an independent man who is not insensitive to the pain of others."

And as for those who believe in conspiracy theories, some say that the thin line that appears near the bard's chin proves that this portrait is of a man wearing a mask. The 'pro-Earl of Oxford wrote WS' Jesuit priest, Charles Sidney Beauclerk (1855-1934) claims that this portrait is of the Earl of Oxford, while the American computer artist, Lillian Schwarz (b.1927) says that this is really a portrait of Queen Elizabeth I.

So the final decision is yours. Is it really a true likeness or not? Next time I will consider some of the other Shakespearean portraits which also claim to be authentic.

For comments please write to me at: wsdavidyoung@gmail.com or to my Facebook page. Thank you.

And now for the details about the murder of Christopher/Kit Marlowe. The version published about this murder at the time claimed that Marlowe was stabbed to death during a drunken brawl and argument about paying the bill - the reckoning (see last paragraph below) in a Deptford pub/brothel. The three guys with him, Ingram, Skeeres and Friser, were all shady members of the criminal underground and may also have been used by the authorities to spy out on Catholics who were thought to be ready to rise up and usurp the Elizabethan regime.

An official inquest into the murder was held soon after where it was established that the popular playwright - the man who had written Doctor Faustus - had been stabbed in the eye and died immediately afterwards. The guilty men were charged but received only short terms of imprisonment. This last point is often taken to prove that the government which had become increasingly fed up with Marlowe's unconventional (and atheistic) behaviour had decided to get rid of him. This was the conventional description of this brilliant writer's unexpected and early demise. The official record of the inquest was uncovered in 1925 by Dr. J. Leslie Hotson at the Public record Office in London.

But this story isn't true claimed an American lawyer, Wilbur Ziegler in 1895. In the preface to his novel, It was Marlowe: A Story of the Secret of Three Centuries, he claimed that Marlowe wasn't killed and went on, together with Sir Walter Raleigh and the Earl of Rutland to write Shakespeare's plays.

Now we fast forward sixty years. In 1955, New York publicist, Calvin Hoffman published his book, The Murder of the Man who was Shakespeare. He stated that he was sure that Marlowe was not murdered in May 1593 and that he, Hoffman, wanted to open the Walsingham family vault in the hope of finding some Marlowe/Shakespeare manuscripts. (Walsingham was Marlowe's friend.) In 1956 he did so, only to find some sand and several coffins. Unfortunately for Hoffman, he was not allowed to open them.

In his chapter on Marlowe in Who Wrote Shakespeare? John Michell writes that it was possible for Marlowe to survive this attempt on his life then go abroad and later return in disguise to continue writing in disguise as Shakespeare. This ties up with the Marlovians' theory that a noise was made about Marlowe's (alleged) death so that the government could officially get rid of him as a spy, and then quietly re-use him as an undercover man to continue unearthing anti-Protestant government plots being cooked by Catholics.

Technically this may have been possible, however, I think this theory is unlikely. The idea that Marlowe continued writing Shakespeare from 1593 until 1613, i.e. remaining hidden from the limelight that he so loved for twenty years seems 'mission impossible.' I am prepared to agree that Marlowe could have agreed to write Shakespeare (the proven name of a known actor) for maybe five years, but twenty years???

Finally, the following quotation from Shakespeare's As You Like It (Act III. sc.iii) is said to be proof by some that Marlowe was indeed dead in or about 1599 when the Bard wrote:

"When a man's verses cannot be understood , nor a man's good wit seconded with the forward child understanding,it strikes a man more dead than a great reckoning in a little room."

Next time I want to take a break from seeing who wrote Shakespeare and instead write about the well-known portraits we have of the Bard and see if they were really depicting our hero.

For comments etc, please write to: wsdavidyoung@gmail.com

Thank you.